As the news about Coronavirus has increased, my son William and I have had many conversations about how church leaders should respond in times like these. Today, he wrote a guest blog on leaders in history who have exemplified the Christian response to crisis.

—Steve

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE—What for many weeks seemed like media-driven hysteria—or at least a distant, localized phenomenon—has now become a tangible global reality.

According to many public health experts, the coronavirus, or COVID-19, has the potential to become one of the greatest pandemics of our lifetimes. We do not know how many will ultimately be affected by the outbreak, nor do we know how many will die. But we do know that the social, economic, and geopolitical effects will be deep and widespread.

How should the church respond in this moment of crisis? And how can pastors provide spiritual leadership for congregations in a time when governments across the world have forbidden public gatherings (including Sunday worship services)? Where can we look for guidance and wisdom?

Though this may be a new experience for us in the twenty-first century, it is not new in the two-thousand-year history of the church. Plagues and pandemics have come and gone, but the church, by God’s grace, has remained and continues to spread to every nation. What can we learn from church history that will help the church in our present moment? How did our brothers and sisters who came before us respond in the face of panic and pandemic? What characteristics mark the people of God in a time of widespread fear and imminent danger?

When I look at the history of the church, I see four unique characteristics that have caused the church to shine in times of darkness: calm, compassion, creativity, and courage.

CALM

In the summer of 1854, a young and inexperienced pastor in London found himself in the middle of a terrifying cholera outbreak. As the recently hired pastor of New Park Street Chapel, twenty-year-old Charles Spurgeon did his best to serve his new congregation by visiting the sick and dying.

At the height of the epidemic, Spurgeon was conducting funerals almost every day, and he began to slip into fear and despair:

I became weary in body and sick at heart. My friends seemed falling one by one, and I felt or fancied that I was sickening like those around me . . . I felt that my burden was heavier than I could bear, and I was ready to sink under it.

However, one day when Spurgeon was walking home from yet another funeral, he noticed a handwritten paper posted in a shoemaker’s window with these words:

Because thou hast made the Lord, which is my refuge, even the Most High, thy habitation; there shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling (Psalm 91:9–10).

Spurgeon writes of that moment:

The effect upon my heart was immediate. Faith appropriated the passage as her own. I felt secure, refreshed, girt with immortality. I went on with my visitation of the dying in a calm and peaceful spirit; I felt no fear of evil, and I suffered no harm.

Though fear and panic are natural human responses to global pandemics, the Christian, and in particular the Christian leader, is called to embody a different spirit. It is our calm in the face of death and uncertainty that really shows who we are and whose we are.

Many years later, there was another cholera outbreak in London, but Spurgeon was ready. His spirit was calm and poised to be used by God. Speaking to a group of pastors, he charged:

And now, again, is the minister’s time; and now is the time for all of you who love souls. You may see men more alarmed than they are already; and if they should be, mind that you avail yourselves of the opportunity of doing them good. You have the Balm of Gilead; when their wounds smart, pour it in. You know of Him who died to save; tell them of Him.

In the end, the calm of the Christian in the face of crisis is not a display of stoicism. It’s not a display of self-reliance. It’s a display of Jesus—the only human who has ever been perfectly calm in a storm.

So here’s the question: what is the climate of your soul in this moment of global crisis? Do you look more like Spurgeon during the first cholera outbreak—weary, afraid, and despairing—or do you look more like Spurgeon during the second cholera outbreak—full of faith, saying, “now is the minister’s time?”

COMPASSION

In August of 1527, the bubonic plague came to Wittenberg, home of Martin Luther and the nascent Protestant Reformation. Immediately, people began to flee the city, knowing from centuries of experience that the appearance of the black death in a town could mean that over half of the population could die in a matter of months.

Despite pleas from his friends and colleagues at the university, Luther and his pregnant wife, Katharina, decided to stay in Wittenberg to minister to the sick and the fearful. They even opened their home to care for those infected with the plague. Reflecting on his decision, Luther wrote:

Those who are engaged in a spiritual ministry such as preachers and pastors must likewise remain steadfast before the peril of death. We have a plain command from Christ, “A good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep but the hireling sees the wolf coming and flees” (John 10:11). For when people are dying, they most need a spiritual ministry which strengthens and comforts their consciences by word and sacrament and in faith overcomes death. . .

Luther’s basis for compassion was simple. If we want to love God, we must start by loving our neighbor—especially in a moment of crisis when our natural inclination is toward survival and self-preservation.

There you hear that the command to love your neighbor is equal to the greatest commandment to love God, and that what you do or fail to do for your neighbor means doing the same to God. If you wish to serve Christ and to wait on him, very well, you have your sick neighbor close at hand. Go to him and serve him, and you will surely find Christ in him. . .

Interestingly, though Luther refused to leave Wittenberg, he was not dogmatic about every single citizen staying. He primarily emphasized the obligation that pastors had to their congregations and that individual Christians had to their neighbors. If those people were taken care of, then fleeing the plague was wise in Luther’s opinion.

So here’s the question: who has God called you to serve in this time of crisis? If you are a pastor, how can you extend compassion and comfort to people in your church and on your staff in a time when many churches around the world are forbidden to meet? If you are a campus missionary, how can you serve students in your city at a time when classes have been cancelled and dorms have been vacated? If you are a lay leader, how can you serve your neighbor in this time of fear and uncertainty? Though it will take creativity to serve in this unique time, it all starts with having a heart of compassion.

CREATIVITY

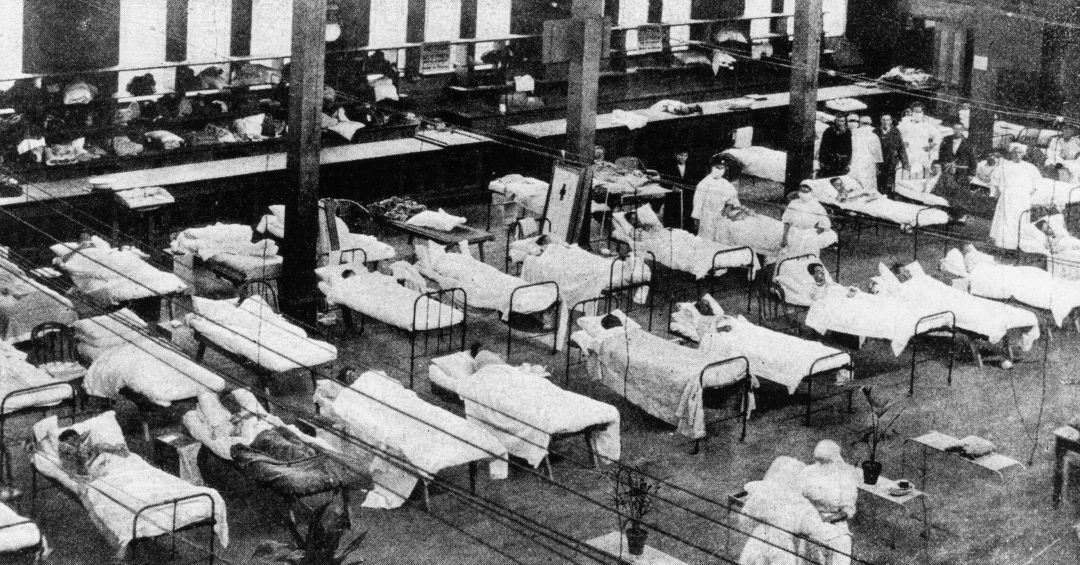

In March of 1918, the United States was hit by the influenza pandemic, which in the course of a year would claim over 50 million lives worldwide. In the midst of one of the deadliest epidemics in human history, local and state governments across the United States began forbidding public gatherings, including Sunday worship services.

Some church leaders grumbled and some protested, but most complied with the public health measures. However, rather than anxiously waiting for the quarantine to lift, pastors around America began to find creative ways to minister despite the ban on public worship.

For example, in many cities, pastors would write abbreviated sermons that would be published by the local newspaper in the Sunday edition so that their quarantined parishioners could read the sermon at home. One baptist pastor in Louisville, Kentucky, took the opportunity to remind his readers:

The days of the church’s greatest power have not been when believers were cozy and comfortable in magnificent houses of worship. The people have been more powerful in saving the world when persecution shut them out of the synagogues and forced them to find refuge for fellowship and worship in the dens and caves of the earth.

In a Birmingham newspaper, another pastor encouraged people to embrace the opportunity to gather to worship in homes as was the practice in the early church:

This will have to be done in Birmingham and in many cities for the next several Sundays, since the ban has been put on public assemblies . . . If there is singing and praying and Bible reading and exhortation to godliness in the church, there ought to be exactly these same things in the home, particularly at a time like this.

Not only did Christians find creative ways to hear the word and to gather for worship, but they also found unique ways to serve their neighbors in the midst of the pandemic. For example, in Worcester, Massachusetts, a Catholic women’s club regularly visited those infected with the flu, bringing them food and clothing. In the same city, several Protestant churches teamed together to care for recently orphaned children in the community who had lost their parents in the epidemic.

Like Luther and Katharina centuries earlier, Christians across America found creative ways to “be the church” even when they were not permitted to “go to church.”

So here’s the question: how can we find creative ways to love our neighbors and our cities during this moment of crisis? How can we be faithful to God’s calling on our lives and our church communities today? What kinds of opportunities are opening up to preach the gospel, make disciples, and even plant churches that would have never been present in the days before COVID-19 began to disrupt life as we know it across the globe?

COURAGE

In order to be calm, compassionate, and creative in the midst of a deadly pandemic, we need courage.

It took courage for twenty-year-old Charles Spurgeon to keep visiting the sick and burying the dead, even when he was fearful and weary.

It took courage for newly married Martin and Katharina Luther to stay in Wittenberg and open their home to care for the sick—all while Katharina was pregnant with their first child!

It took courage for ordinary church women in Massachusetts to take on the care of the orphans in their community in the midst of the deadliest flu epidemic in history.

Though courageous action always involves personal risk, even someone as bold as Luther was careful to point that courageous Christians need not be foolish ones:

I shall fumigate, help purify the air, administer medicine, and take it. I shall avoid places and persons where my presence is not needed in order not to become contaminated and thus perchance infect and pollute others, and so cause their death as a result of my negligence. If God should wish to take me, he will surely find me and I have done what he has expected of me and so I am not responsible for either my own death or the death of others. If my neighbor needs me, however, I shall not avoid place or person but will go freely, as stated above.

Luther believed it was his duty to take certain risks to serve his neighbor, but he also believed it was duty to take certain precautions to serve the larger community.

Though this is an important caveat, which Luther himself made repeatedly, for most of us, the problem is not that we lack caution but rather that we lack courage. Luther believed strongly that fear and anxiety were from the devil and that the only way to defeat him was with bold and courageous action and a little trash talk:

Because we know that it is the devil’s game to induce such fear and dread, we should in turn minimize it, take such courage as to spite and annoy him, and send those terrors right back to him. And we should arm ourselves with this answer to the devil:

“Get away, you devil, with your terrors! Just because you hate it, I’ll spite you by going the more quickly to help my sick neighbor . . . No, you’ll not have the last word! If Christ shed his blood for me and died for me, why should I not expose myself to some small dangers for his sake and disregard this feeble plague? If you can terrorize, Christ can strengthen me. If you can kill, Christ can give life. If you have poison in your fangs, Christ has far greater medicine. Should not my dear Christ, with his precepts, his kindness, and all his encouragement, be more important in my spirit than you, roguish devil, with your false terrors in my weak flesh? God forbid! Get away, devil. Here is Christ and here am I, his servant in this work. Let Christ prevail! Amen.”

CONCLUSION

Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles. And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us, fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of our faith (Hebrews 12:1–2)—our model and our source of calm, compassion, creativity, and courage.