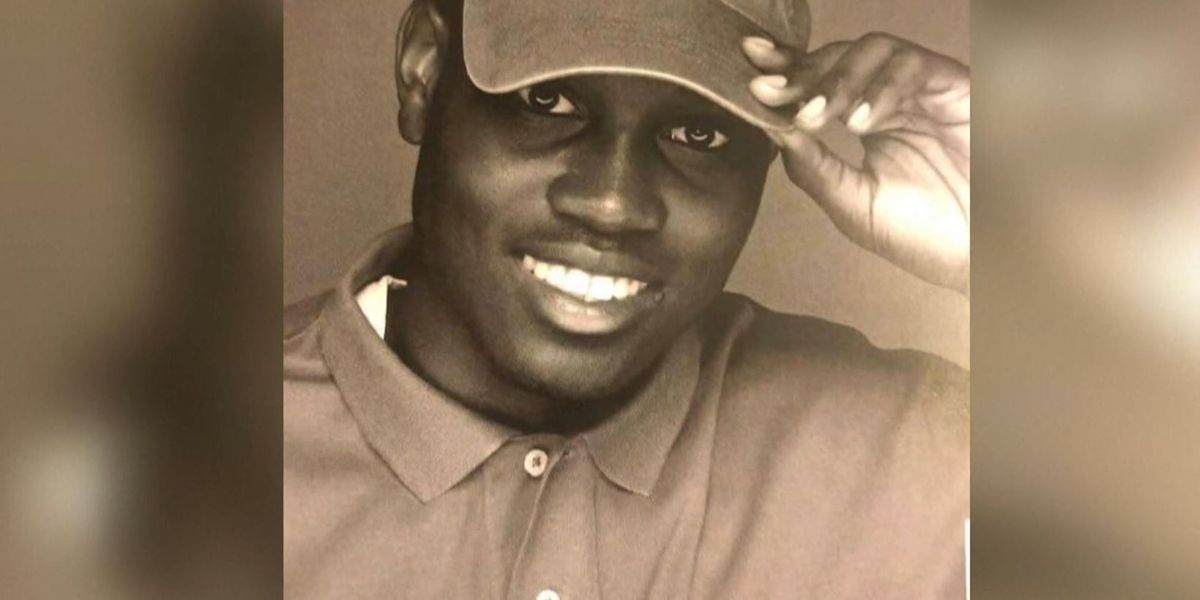

As the leader of a global movement, I make it a point not to comment on national issues. However, as has been the case with many other current events, my son, William, and I recently had a conversation about the violent killing of Ahmaud Arbery. I asked him to share his thoughts in light of a surprisingly relevant piece of Murrell family history.

William S. Murrell, Jr.—For those unfamiliar with the tragic death of Ahmaud Arbery (who was shot while jogging near his home), I recommend reading this article for a detailed analysis of the facts as we know them today.

As I’ve grappled with how to respond (privately and publicly) to yet another needless killing of an unarmed black man, I’ve found strange solace from the biography of a distant ancestor of mine (Same family tree, but a different branch) named John Murrell—who became (in)famous in the 1820s and 30s as a bandit, horse thief, and slave-stealer in the southern United States.

As a slave-stealer, Murrell would help African American slaves escape from their masters and would pretend to be a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. However, the journey north to freedom had a twist: Murrell (with the cooperation of the recently freed slave) would resell the slave to a new master and then help them escape a few days later. Murrell would do this several times on the journey north with the promise that when they reached freedom, he would split the profits with the newly freed slave so that he or she would have money to start their new life. But Murrell never came through. Either he would abandon the slave with their new master if things got too complicated; or worse, he would kill the nameless “negro” once they got close to the border.

Reading and reflecting on Murrell’s biography has helped me process Ahmaud Arbery’s death in at least four ways.

First, Murrell’s biography has provided me with a horrifying yet salutary reminder of human depravity and sin. Since my last name is not very common, it has been surreal to see the name “Murrell” referred to so frequently as the agent of such violence and evil (murder, robbery, slavery, rape, etc). While reading the accounts of Murrell’s breathtakingly depraved deeds—particularly towards black people—I find myself subconsciously trying to disassociate from my ancestor and his sins. But every time I make this mental move, I sense the Holy Spirit reminding me that his blood runs in my veins. Apart from God’s grace, I am no more righteous than John Murrell and just as capable of unspeakable evil. Thus, I have begun reading Murrell’s biography as a picture of who I could have been had I lived in Tennessee in 1820 and not been redeemed by Jesus. To make matters even more personal, one of John Murrell’s main accomplices was his older brother, William S. Murrell. (To clarify, this is just coincidence; I was not named after him, nor was my father. But the coincidental name match was surreal nonetheless.)

Second, Murrell’s biography reminds me that sadly, Christianity can become a cover for racism and injustice. It turns out that besides being a bandit and a slave-stealer, John Murrell also had another life as an imposter Methodist circuit rider. On one day, we find Murrell preaching at a camp meeting (or outdoor revival) in Kentucky. On the next, we find him stealing the revival participants’ horses and slaves and heading to the next town. For Murrell, the persona of the Methodist preacher was the perfect cover for his other work. It gave him credibility with local communities as he traveled around the South. Though Murrell’s duplicity may have been more blatant than most, for generations, white Americans have hidden their racism behind a veneer of religion. For too long, Christians have dressed up their racism with theological arguments and the general perception of being respectable “God-fearing” citizens—which is how some defenders are characterizing Ahmaud Arbery’s killers.

Third, Murrell’s biography provides me with historical perspective on how easily and frequently our societies (whether in the nineteenth or twenty-first century) devalue human life. When Murrell was finally brought to justice in 1834, it was not for murdering African-American slaves but for stealing “property” from white slave owners. Throughout his biography, written shortly after his death, it’s amazing how inconsequential Murrell’s black victims appear in the eyes of the white storyteller. While the murders of black men and women are never condoned or celebrated by Murrell’s nineteenth-century biographer, his black victims are also never mourned—even named. I imagine that this historic devaluing of black lives (and deaths) is why events like the killing of Ahmaud Arbery can be so traumatic for African Americans today. It reminds them that their lives (in the eyes of some) continue to be undervalued nearly two centuries after emancipation. Remember, Arbery was killed on February 23, 2020, and no one was arrested or investigated, even though the police on scene knew who pulled the trigger. It was only after a video of the killing surfaced in early May that arrests and investigations were renewed.

Finally, Murrell’s biography offers me hope for justice in our day. I was fascinated to discover that Murrell’s capture in 1834 came at the hands of Tom Brannon, a black slave from Florence, Alabama, who outsmarted Murrell at his own game. Murrell had kidnapped Brannon and tried to enlist him in his grand scheme to start a slave revolt in the south. However, Brannon double-crossed Murrell and delivered him to the authorities, who rewarded him with the $100 bounty (a lot of money in 1834) for aiding in the capture of the most-wanted man in America. At our present moment when justice so often seems to elude the black community, the story of Tom Brannon gives me hope that justice will be served in the case of Ahmaud Arbery.

Not only does Murrell’s biography give me hope for justice for Ahmaud Arbery and his family but it also gives me hope for the redemption of his killers.

According to Murrell’s biography, during his ten years in prison, Murrell repented and experienced a genuine religious conversion. He was regularly visited by (real) Methodists ministers who preached the gospel to a broken man who had spent his entire adult life lying, stealing, and killing—all under the guise of being a Methodist preacher. When he was released from prison in 1844, he became a blacksmith (a trade he learned in prison), and literally spent the remaining months of his life (before dying of tuberculosis) turning swords into plowshares. Likewise, regarding Ahmaud Arbery’s killers, I am praying for justice to prevail. I am also praying for their redemption and reconciliation.

If God can redeem John Murrell, he can redeem anyone. And if God can bring both justice and redemption in 1844, he can do it in 2020.